Iturbide

by Cedrian López Bosch Martineau

The cédulas or billetesCédula is a document that recognizes a debt or an obligation. A billete is a promissary note to pay a specified amount. issued in 1823 to meet the resource needs of the First Empire are widely mentioned in historical-economic and numismatic literature for being the first attempt to issue paper money of the newly independent state. Despite this, it is striking that there are few in-depth studies on them; most of it is limited to their physical description and the reproduction of the decrees of 20 December 1822 and 11 April 1823 with which they were issued and demonetized and accepts without question the conclusions of various authors of the nineteenth century about their failure due to their short duration, and even attributes some responsibility to them in the fall of the empire.

Here I seek to offer a more complete view of the issue, circulation, amortization and destruction of these certificates, from primary sources of the time and review the interpretation that has been given of them. Certainly, with only four months of duration, their scope was limited, but even if their fate was linked to that of the short-lived government that issued them, you cannot categorically conclude that they were a resounding failure because they served to fulfill their objective, at least partially. As we will see below, despite the difficulties of the time, they increased the liquidity of the imperial government, followed the guidelines for their circulation and use, and even continued to be used months and even years later.

This work emerged in three parts; the first was done by Roxana Álvarez who analyzed the paper money files of the Archivo Nacional de la Nación (AGN), including the statistics of the “Book of Exchange of banknotes of the Empire for banknotes printed on the back of the bulls”, as part of an inventory and cataloguing project carried out in 2007-2008 by the Faculty of Economics of the UNAM, from which she derived her Bachelor thesis. In 2015, I found more than a hundred documents dated between 1822 and 1828 from the Román Beltrán Collection in the digital archive of the Center for Studies of History of Mexico (CEHM) with an account of the existing documentation on this issue. Finally, from these came the idea of gathering more information to offer a deeper vision to the numismatic community of the fate of this issue.

This work is delivered in two parts. The first sets out the historical-economic context and describes the printing and distribution of the currency, whilst the second will details it withdrawal and draw certain conclusions.

Historical-economic context

The Bourbon reforms of the last two decades of the eighteenth century brought with them the extraction of significant amounts of metallic cash from New Spain. This, together with the paralysis in economic activity due to the reduction of the labor force and the abandonment and flooding of the mines during the War of Independence and the numerous contributions created to finance the armies, caused the depletion of the nation’s coffers and the dismantling of the tax system. Naturally, when independence was achieved, the population expected this situation to change.

The Regency, from September 1821 to May 1822, and the Empire that began on the 19th of this last month, saw the need to reorganize the entire system, starting with the Public Treasury. It created a Provisional Junta, composed of members of the military, ecclesiastical and economic oligarchies that, while convening a Constituent Congress (February 1822) and appointing the new monarch (May 1822), was given the task of implementing a functional system, particularly in fiscal matters. The Board proposed eliminating multiple extraordinary contributions introduced during the Independence conflagration and reducing the tax burden. Upon taking office, Emperor Iturbide tried to further reduce the fiscal burden but to ensure the functioning of the government and improve the conditions of the army to guarantee the pacification of the country, he saw the need to appeal to specific contributions and the patriotism of the population to promote loans, at first voluntary and later forced, that deepened tensions with the elites of Congress with whom he had already clashed for their opposition to various imperial proposals and the definition of the powers of each of the branches.

At that time, some countries such as France, Holland, Sweden, England and the United States had already used fiat issues to meet urgent needs and government banks were beginning to be created to help manage resources more efficiently. In this context and as part of the debate between the different political options that proposed the creation of institutions and ways of conducting public life in the nascent country, newspapers and pamphlets reproduced similar proposals by relevant personalities.

Thus, among other proposals to solve the pressing problems of the new nation, on 15 May 1822, the Fanal del Imperio Mexicano included the creation of a Banco Nacional to contribute to the recovery of national sovereignty, serve as a collection agent and solve the problems of the means of payment. This project, attributed to the priest Francisco Severo Maldonado Jaime Olveda, “Banca y Banqueros de Guadalajara”, in Cerruti, Mario and Marichal, Carlos (2003), La Banca Regional en México (1870-1930), Mexico, el Colegio de México-FCE., p 294, suggested the establishment of contributions, taking advantage of tithes, and the creation of two million pesos in tlacos, manufactured with an alloy of copper and zinc, to circulate with forced acceptance. The proposal is extremely detailed about the organization, activities and way of raising resources for this bank. With regard to the issue of these tlacos, it describes the exchange of existing provisional currencies for the issue by the government of nominative but endorsable libranzas, which could serve as promises of payment as long as the said small currency was available for exchange El Fanal del Imperio Mexicano, pp 292-294, cit. por Roxana Alvarez, Primer Experimento de Emisión de Papel Moneda en México, thesis to obtain the degree of Licenciada in Economics, Mexico, UNAM, Facultad de Economía, 2008, p 47-48.

Another relevant proposal was presented by Francisco de Paula y Tamariz to Congress to create a financial institution with a presence throughout the territory responsible for lending and acting as a financial agent, the Gran Banco del Imperio Mexicano. According to this proposal, discussed with the then Minister of Finance, Antonio de Medina, the bank had the power to issue “cédulas-promissory notes” or “haré-buenos”, that is, short-term public debt instruments payable at sight, non-nominative, and valid for the payment of all types of transactions in the Empire, of forced acceptance in the payments of duties and taxes in the Customs, savings banks and treasuries. The amount of the suggested issue was four million pesos, in the following denominations: 5, 10, 50, 100, 300, 500 and 1,000 pesos and could only be used in transactions exceeding 15 pesos under the ley de tercio (law of the third), that is, one third in paper and two thirds in cash. Although these debt instruments had an interest of six percent per annum on semi-annual settlements, they were endorsable and could circulate as paper money.

A month after presenting to Congress his evaluation of the country’s financial situation, in October 1822 Minister de Medina proposed to the Mexican Supreme Congress the creation of a direct contribution that would only affect the wealthiest classes and the creation of paper money. With this, he hoped to solve the problem of low collection and meet the country’s financial needs. However, the Congress rejected his proposal, generating a new disagreement with Emperor Iturbide, who decided to dissolve it at the end of that month and put in its place a Junta Nacional Instituyente (National Instituting Board), composed of a group of notables selected by the Emperor among whom were some loyal deputies of the previous Congress. From November of that year, it dedicated itself to finding ways to face the country’s challenges through different commissions; in order to reorganize public finances, the Board established a Finance Commission to study measures introduced in other countries and echoed the proposals in the public debate. In this way, a plan was drawn up that included various temporary measures to meet the needs of the government such as the reinstatement of the alcabala tax, taxes per head, on property, meat and alcoholic beverages and again the creation of paper money. This plan was presented on 5 December 1822 and from it emanated four decrees discussed and approved between the 16th and 18th of that same month.

Issue and distribution of paper money in the Empire

Thus, on 20 December 1822, the Gaceta Imperial de México published the decree authorizing the issue – coincidentally – of four million pesos in paper money of mandatory acceptance for administrative and commercial operations, valid only for the year 1823, in three denominations for the following amounts:

| Denomination | Quantity | Total value |

|---|---|---|

| $1 | 2,000,000 | $ 2,000,000 |

| $2 | 500.000 | 1,000,000 |

| $10 | 100,000 | 1,000.000 |

| 2,600,000 | $ 4,000,000 |

This amount, equivalent to one fifth of the budget for that year (20,328,740 pesos), was intended to cover the deficit of 1822 and generate a reserve. It was determined that they needed to send 2.25 million pesos to the Intendencias (as detailed below) and the rest to the capital.Calculated with information from 1809, the last year with reliable information and stable production before the War of Independence

| Intendencias | $1 | $2 | $10 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guadalajara with Baja and Alta California | 147,892 | 37,446 | 8,282 | 305,604 |

| Puebla with Tlaxcala | 180,000 | 45,000 | 9,000 | 360,000 |

| Veracruz | 135,000 | 33,750 | 6,750 | 270,000 |

| Merida | 45,000 | 11,250 | 2,250 | 90,000 |

| Oaxaca | 70,000 | 17,500 | 3,500 | 140,000 |

| Guanajuato | 110,000 | 27,500 | 5,500 | 220,000 |

| Valladolid | 80,000 | 20,000 | 4,000 | 160,000 |

| San Luis Potosí with Nuevo Reino de León, Nuevo Santander, Coahuila and Texas | 120,978 | 30,245 | 6,049 | 241,958 |

| Zacatecas | 32,524 | 8,131 | 1,626 | 65,046 |

| Durango with New Mexico | 60,000 | 15,000 | 3,000 | 120,000 |

| Arizpe | 20,000 | 5,000 | 1,000 | 40.000 |

| Provinces of Guatemala | ||||

| Chiapa | 12,000 | 3,000 | 600 | 24,000 |

| Comayahua | 12,000 | 3,000 | 600 | 24,000 |

| San Salvador | 22,000 | 6.000 | 1,000 | 44,000 |

| Nicaragua | 22,000 | 6.000 | 1,000 | 44,000 |

| Guatemala | 50,000 | 12,500 | 2,500 | 100,000 |

| Total | 1,119,394 | 281,322 | 56,657 | 2,248,608 |

Amount of paper money to be remitted to the provinces in 1823 (CEHM Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.10.468.1)

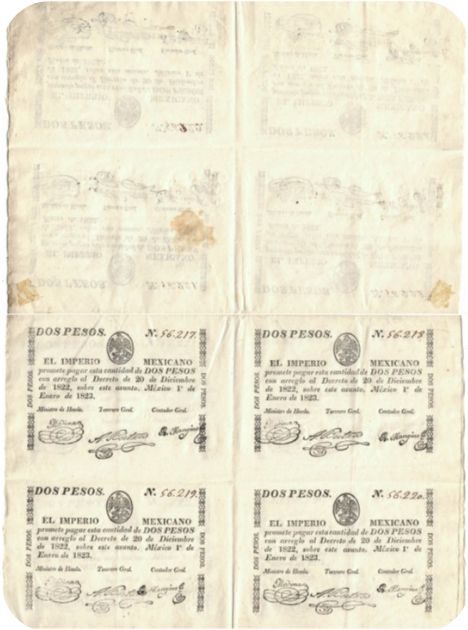

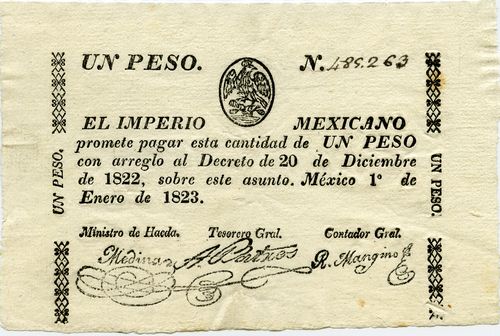

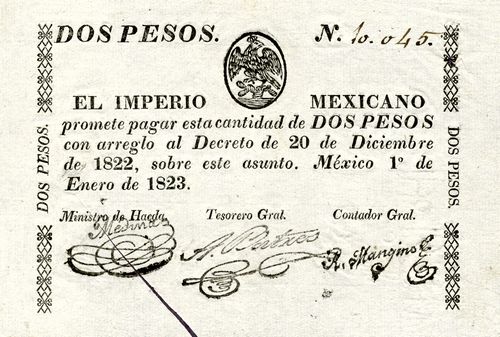

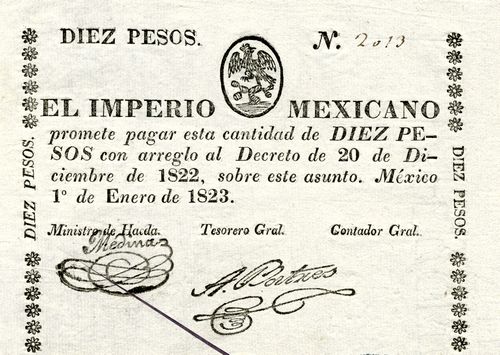

These certificates were prepared by the Government Press, under the charge of Juan Wenseslao Barquera, on sheets of white Spanish paper medio folio approximately 42 x 31 cm, with the filigree “No Io” on one side and the Torre de los Guarro and “JHP ROMUGOSA” on the other. Eduardo Rosovsky, “The Paper Money of Iturbide” in Boletín Numismático, No. 70, January-March 1971. Although Rosovsky describes this watermark it might have been that the printers used paper from various sources and so watermark need not be an easy indicator of a note’s genuineness or falsity.

M11d $2 El Imperio Mexicano uncut sheet of four

Each sheet had eight printed notes, four on each side, probably so that they could be folded and numbered more easily.

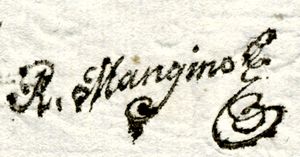

On them, the Imperial shield appears with an eagle with a crown on a cactus centered at the top; the denomination in letter in the upper left and in the left (in italics) and right margins; the manuscript number in the upper right corner, and below the shield the legend: “The Mexican Empire promises to pay the amount of [one, two or ten] pesos in accordance with the Decree of 20 December 1822, on this matter. Mexico, 1 January 1823”. Below were the signatures of the aforementioned Minister of Finance, Antonio de Medina; the General Treasurer, Antonio Batres; and, of the General Accountant, Rafael Mangino.

|

On Independence the Junta Nacional Instituyente appointed him Secretary of War and Navy (Secretario de Guerra y Marina), a position he left on the orders of Emperor Iturbide to organize the various branches of the Public Treasury, a task in which he remained nine months until a week after Iturbide's abdication (1 July 1822 to 1 April 1823). He was called to office with the purpose of correcting the budget deficit accumulated for more than a decade and the administrative disorder suffered by the newly independent state, aggravated by a paralysis in production. The amount of the emperor's military and pomp expenditure not only made it impossible to correct the deficit but also caused the Treasury's lack of liquidity, a situation Medina attempted to correct with his issue of paper currency for military and administrative payment. This proved a failure in the face of the growing distrust and opposition of Mexico City's elite and the growing reaction of the provinces that ended with Iturbide's resignation, following an uprising in February 1823. Upon leaving office, Antonio de Medina became part of of the Secretaría de Guerra y Marina and a senator in the first federal Senate. He died in Mexico City on 29 July 1827. |

|

| Antonio Batres had been Tesorero de la Hacienda Pública de Nueva España for the last viceroyAGN, Indiferente virreinal, Real Hacienda, caja 6101, exp. 23 letter to Viceroy Conde de Venadito, Mexico City, 8 November 1820. |  |

|

He died in Mexico City on 14 June 1837. |

|

The one and two pesos notes have margins with rhomboid figures on both sides, and those of ten with the shape of a flower. The reverse is blank. According to the decree, these notes had to have marks and signs necessary to prevent their falsification, but as will be seen later they did not have them or they were not effective.

The decree consisted of 14 articles through which the issue, use and amortization of these certificates was described. The Minister of Finance sent it to all the civil, military and ecclesiastical authorities of the Empire on 21 December, with the instruction to publish it and enforce it. By this decree, as of 1 January 1823, a third of the salaries and civil and military pensions, and the payments made by the offices of the Treasury, had to be made through these certificates, the rest in metallic currency. The law of the third would also apply to the payments of taxes and contributions to the Treasuries and Administrations of the Treasury and, although some current authors point out the opposite, it also operated for civil and judicial payments greater than three pesos, as evidenced by the records of the notaries, under the penalty of a fine for those who refused to accept the notes.

As can be seen, this decree covered the creation of a means of fiduciary payment, temporarily, to pay for all types of transactions, solve the government deficit and address the lack of currency, as proposed by Francisco S. Maldonado and Francisco de Paula Tamariz, even in the amount suggested by the latter, thus avoiding appealing to a new loan that would surely have been rejected by the wealthy classes, and its forced acceptance through the law of the third.

The Chief Treasury Officer, Mariano Larraguibel, was responsible for the counting, stamping and numbering of the notes. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.10.454. Some modern authors say that they were sent out already signed, but some document mentions that they were sent with the stamps of the corresponding signatures. The sheets of uncut notes were sent in reamsA ream is composed of 20 hands (manos) of paper, these in turn of five booklets (cuadernillos) and in turn these of five sheets (hojas), that is, each ream consists of 500 sheets of paper. to the Intendants of the Provinces, who had to deliver them in turn to the Main Treasury to be cut and put into circulation, with the obligation to make monthly reports of their balance sheets and the amounts that they had amortized.

Although, as mentioned above, the intention was to put the decree into force throughout the territory of the Empire on the first day of 1823, various documents of the time explain the difficulties in achieving this, not only because of logistical complications, but also because of the lack of sufficient printed quantities. The short time between the decree and the date of its entry into force did not allow the Government Printing House to have sufficient notes; of the total of 650 reams of paper required, on 21 December 1822 only three reams of printed notes were delivered to Larraguibel and during the rest of the month a further 87 reams, that is, before the entry into force of the decree they only had 360,000 notes (which still had to signed and numbered) to be distributed throughout the territory. Between 21 December 1822 and 13 January 1823 Larraguibel received almost daily deliveries from the printers, a total of 19 deliveries of, in all, 248 reams (188 of $1 notes, 43 of $2, and 17 of $10). By February 6, Larraguibel mentioned 277 reams had been printed. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11.558.

For this reason, consideration was given to postponing payments or withholding the third part of paper money except in duly documented cases of urgency. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.10.460 As will be seen below, this was clarified on a case-by-case basis.

Another difficulty lay in the time and lack of security to distribute them. The shipments were made by courier, that is, carried on horseback or by mules and with a postillion. This meant that a shipment from the capital to Veracruz could take about a week. For example, on January 29 several remittances left for the most distant provinces, but the Nicaraguan intendencia did not receive notification of their shipment until February 26 and replied that as soon as they received them they would acknowledge it. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11.501 but we do not know if it really happened. Additionally, distribution challenges were also associated with the lack of road safety. Some shipments were made in chests with three keys Roxana Alvarez Nieves, El papel moneda de Agustín de Iturbide, conference at the Mexican Academy of History, 22 October 2015 as a security measure, others suggested separating them into different batches to reduce the risk of contingency or loss. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.10.490

As soon as they received the decree and had to start applying it, the different authorities and economic agents began to raise doubts and ask the Minister of Finance for exceptions. On 30 December, the Monte de Piedad asked to be considered exempt given its social nature. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.10.461 On 3 January, the directors of the lottery and tobacco confirmed that the procedure should be followed in tobacco stores and the tobacco administration and explained how they should redeem the amortized paper by papel vivo (live paper). Gaceta del Gobierno Imperial de México, Tomo I, Núm. 3, 3 January 1823, p 4 The next day, it was pointed out that the law of the third would not apply to the introduction of metals to the Mint (Casa de Moneda). ).Gaceta del Gobierno Imperial de México, Tomo I, Núm. 3, 3 January 1823, p 4 On 11 January, Francisco José Bernal reported that the Ministry of Finance had resolved to modify the proportion of the payments to soldiers to only 20 percent to avoid abuses and this would not be given to them in paper but would be used for investment in their living conditions. Circular No. 59, CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo I-2.14-38 1058

Other allegations concerned the poorer classes and commented on the need to allow the exchange of one-peso notes for cash. Although the decree was clear that those who received wages of less than three pesos would be paid only in cash and the law of the third would apply only for payments greater than that amount, the problem was that those who received their payment in notes and had small expenses were forced to sell them at a discount. This happened from the very week of their issue. The resolution emphasized paying in silver to those who earned less than three pesos. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.12.628 but omitted to clarify the way to proceed when there was no paper to pay the third or when the officials of some office did not accept this transfer. Other proposals suggested the government support the change and/or issue other minor denominations, but these were scrapped. . CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.12.627

Faced with the delay in the arrival of paper money, some customs and offices wondered if they should wait, so as not to violate the decree, or accept payments only in cash. The latter was generally opted for until this fiat currency arrived, which took much of January, while communications came and went. There were also offices which refused to accept payment and were forced to accept them. . CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.12.628 Doubts were raised as to whether previous debts should follow the law of the third and the question was concluded in the affirmative. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.12.628

These doubts were natural for a society accustomed to gold and especially silver coins. Given the initial discredits, the Empire issued a new decree on 10 January 1823 to justify the need for this means to face the situation, emphasizing that the currency should be taken at par and that it would have a short duration, since they would be amortized within a year.

However, there is also a record of the effort of multiple people to use them in daily commercial transactions as stated in the notarial protocols, Larraguibel’ communications with the Consulate of Merchants of Mexico City and the requests from various parts of the Empire for the shipment of more paper money. Roxana Álvares, “De bancos y fracasos: Tres ejemplos para el caso mexicano, 1774-1837”, in Legajos, Boletín del Archivo Generalde la Nación, Vol. 7 Núm. 3, January-March 2010, pp 75-98

For a reason that I still do not know, on 31 January 1823 it was ordered to make a count of the printed and issued banknotes, and to collect the printed and blank paper in the hands of the Government Printing House and the manager Larraguibel. This reported the printing of 1,018,000 notes (797,000 of one peso; 184,000 of two pesos and 37,000 of ten pesos) with a face value of 1,535,000 pesos sent to the treasuries, commissioners and intendancies, 23,022 more unused notes and 67,090 of ten pesos had not been restamped or numbered. That is, only 277 reams of paper had been used and it was instructed to use the rest for other purposes and to destroy those that had been printed but not issued CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII.4.11.558. Mariano Larraguibel continued to be in charge of the operation.

| Date | $1 | $2 | $10 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of notes | $ | ||||

| 1. Provinces | |||||

| Guadalajara with Baja and Alta California | 29 December 1822 | 12,000 | 3,000 | 600 | 24,000 |

| n/d | 12,000 | 3,000 | 600 | 24,000 | |

| Puebla with Tlaxcala | 29 December 1822 | 17,000 | 3,000 | 600 | 29,000 |

| n/d | 17,000 | 3,000 | 600 | 29,000 | |

| Veracruz | 29 December 1822 | 10,000 | 3,000 | 600 | 22,000 |

| n/d | 10,000 | 3,000 | 600 | 22,000 | |

| Merida | 29 December 1822 | 4,000 | 1,000 | 200 | 8,000 |

| 29 January 1823 | 4,000 | 1,000 | 200 | 8,000 | |

| Oaxaca | 29 December 1822 | 6,000 | 1,500 | 300 | 12,000 |

| n/d | 6,000 | 1,500 | 300 | 12,000 | |

| Guanajuato | 29 December 1822 | 9,000 | 3,000 | 300 | 18,000 |

| n/d | 9,000 | 3,000 | 300 | 18,000 | |

| Valladolid | 29 December 1822 | 7,000 | 1,500 | 300 | 13,000 |

| n/d | 7,000 | 1,500 | 300 | 13,000 | |

| San Luis Potosí with Nuevo Reino de León, Nuevo Santander, Coahuila and Texas | 29 December 1822 | 10,000 | 2,000 | 400 | 18,000 |

| n/d | 10,000 | 2,000 | 400 | 18,000 | |

| Zacatecas | 29 December 1822 | 6,000 | 1,000 | 200 | 10,000 |

| n/d | 6,000 | 1,000 | 200 | 10,000 | |

| Durango with New Mexico | 29 December 1822 | 3,500 | 500 | 100 | 5,500 |

| n/d | 3,500 | 500 | 100 | 5,500 | |

| Arizpe | 29 December 1822 | 1,500 | 750 | 3,000 | |

| n/d | 1,500 | 750 | 3,000 | ||

| Provinces of Guatemala | |||||

| Chiapa | 29 January 1823 | 2,000 | 500 | 100 | 4,000 |

| Comayahua | 29 January 1823 | 2,000 | 500 | 100 | 4,000 |

| San Salvador | n/d | 3,666 | 1,000 | 166 | 7,326 |

| Nicaragua | 29 January 1823 | 3,666 | 1,000 | 166 | 7,326 |

| Guatemala | n/d | 8,333 | 2,083 | 416 | 16,659 |

| Subtotal Provinces | 191,665 | 45,583 | 8,148 | 364,311 | |

| 2. General Treasury (Mexico) | |||||

| 30 December 1822 | 75,000 | 10,000 | 2,000 | 115,000 | |

| 13 January 1823 | 125,000 | 20,000 | 2,000 | 185,000 | |

| n/d | 10,000 | 1,000 | 30,000 | ||

| 28 January 1823 | 38,494 | 9,500 | 1,900 | 76,494 | |

| 3 February 1823 | 140,000 | 32,000 | 10,000 | 304,000 | |

| 3 February 1823 | 1,841 | 667 | 702 | 10,195 | |

| Subtotal General Treasury | 380,335 | 82,167 | 17,602 | 720,689 | |

| 3. For referral to the following individual subjects | |||||

| Pablo Escandón (Puebla) | 29 January 1823 | 25,000 | 6,250 | 1,250 | 50,000 |

| Francisco Venancio del Valle (Guadalajara) | 29 January 1823 | 25,000 | 6,250 | 1,250 | 50,000 |

| Rafael Leandro Echenique (Veracruz) | 29 January 1823 | 25,000 | 6,250 | 1,250 | 50,000 |

| Rafael Bracho (Durango) | 29 January 1823 | 25,000 | 6,250 | 1,250 | 50,000 |

| Ignacio Villalobos (SLP) | 29 January 1823 | 25,000 | 6,250 | 1,250 | 50,000 |

| Cayetano Gomez (Valladolid) | 29 January 1823 | 25,000 | 6,250 | 1,250 | 50,000 |

| Ignacio Goitia (Oaxaca) | 29 January 1823 | 25,000 | 6,250 | 1,250 | 50,000 |

| Manuel Fernández Carral (Zacatecas) | 29 January 1823 | 25,000 | 6,250 | 1,250 | 50,000 |

| Juan Antonio de Beistegui (Guanajuato) | 29 January 1823 | 25,000 | 6,250 | 1,250 | 50,000 |

| Subtotal individuals | 225,000 | 56,250 | 11,250 | 450,000 | |

| Total distributed | 797,000 | 184,000 | 37,000 | 1,535,000 | |

| Useless | 18,052 | 4,696 | 274 | 23,022 notes |

|

| Unstamped | 1,041,022 notes |

||||

| Unnumbered | 67,090 | 67,090 notes |

|||

| Total | 815,052 | 188,696 | 104,354 | ||

Balance of banknotes delivered to treasuries, useless and unfinished as at 6 February 1823 (Report by Mariano Larragibel)

(CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4. 10. 558)

These figures do not necessarily coincide with other counts. At the beginning of March, a figure of 1,654,500 pesos was handled between distributed and treasury stocks; April counts mention 1,328,063 pesosCEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11.512 and 1,929,978 pesos in useful, useless and amortized notes to be incinerated; Extract 11 on Paper Money prepared in 1825 refers to an issue of 2,086,018 pesos at the end of January 1823; and the count dated 3 November 1823 by Ildefonso Maniau as part of the report of Finance Minister Arrillaga to Congress on 12 November 1823 mentions the printing of 2,395,000 pesos, of which only 1,066,869 pesos circulated. These figures were later taken up by Lucas Alamán, although he points out that only 460,299 could be made. Lucas Alamán, History of Mexico: from the first movements that prepared its independence in the year of 1808 to the present time, Book II page 685

A relevant aspect of Larraguibel’s count is the penultimate part of it, which includes the names of some individuals in nine of the most important provinces. An equal number of well-known merchants “with knowledge, probity and love of country” were commissioned to change paper money as a private transaction (negociación particular). In the absence of paper money in the treasuries, these individuals were commissioned, because they were merchants with a great need for this medium of exchange to pay the duties corresponding to their activities, “they were empowered ... so that they cannot verify at par the exchange for silver, they do so with the least possible exchange rate (agio), which may not exceed a loss of four percent.” CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.12.633 Although 50,000 pesos (25,000 pesos of one peso; 6,250 two-peso notes and 1,250 10-peso notes) were considered as the sum to be given to each one, only one-third of that amount was given to each of threm. All except Ignacio Goitia of Oaxaca thanked the honor that had been extended to them and placed themselves at the orders of the emperor to fulfill his decision. Juan Antonio de Beistegui and Venancio del Valle suggested sending paper money to other cities to facilitate its circulation and the first suggested looking for people of reputation and wealth in towns. Extract 19CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4 12.633 pp 12-14 says that only in Guadalajara, Durango, Zacatecas and Guanajuato were these notes changed and in view of the problems of carrying out the exchange they were instructed to deliver to their respective intendancies what they had either in changed cash or in paper.

Issues

$1 notes

M10a $1 El Imperio Mexicano

M10a $1 El Imperio Mexicano

| Date of issue | Date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

|

| 29 December 1822 | 1 January 1823 | 86,000 | $ 86,000 | includes numbers 43389 to 489263 | ||

| 30 December 1822 | 75,000 | 75,000 | ||||

| 13 January 1823 | 125,000 | 125,000 | ||||

| 28 January 1823 | 38,494 | 38,494 | ||||

| 29 January 1823 | 22,666 | 22,666 | ||||

| 307,999 | 307,999 | |||||

| 3 February 1823 | 140,000 | 140,000 | ||||

| 6 February 1823 | 1,841 | 1,841 | ||||

| 18,052 | unusable | |||||

| 815,052 |

$2 notes

M11c $2 El Imperio Mexicano

M11c $2 El Imperio Mexicano

| Date of issue | Date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

|

| 29 December 1822 | 1 January 1823 | 20,250 | $ 40,500 | includes numbers 10138CNBanxico #10700 to 96291 | ||

| 30 December 1822 | 10,000 | 20,000 | ||||

| 13 January 1823 | 30,000 | 60,000 | ||||

| 28 January 1823 | 9,500 | 19,000 | ||||

| 29 January 1823 | 5,250 | 10,500 | ||||

| 76,333 | 152,666 | |||||

| 3 February 1823 | 32,000 | 64,000 | ||||

| 6 February 1823 | 667 | 1,334 | ||||

| 4,696 | unusable | |||||

| 188,696 |

$10 notes

M12b $10 El Imperio Mexicano

M12b $10 El Imperio Mexicano

| Date of issue | Date on note | from | to | total number |

total value |

|

| 29 December 1822 | 1 January 1823 | 3,600 | $ 36,000 | includes numbers 259CNBanxico #10701 to 2255 | ||

| 30 December 1822 | 2,000 | 20,000 | ||||

| 13 January 1823 | 3,000 | 30,000 | ||||

| 28 January 1823 | 1,900 | 19,000 | ||||

| 29 January 1823 | 866 | 8,660 | ||||

| 14,932 | 149,320 | |||||

| 3 February 1823 | 10,000 | 100,000 | ||||

| 6 February 1823 | 702 | 7,020 | ||||

| 67,090 | unnumbered, unstamped | |||||

| 274 | unusable | |||||

| 104,364 |

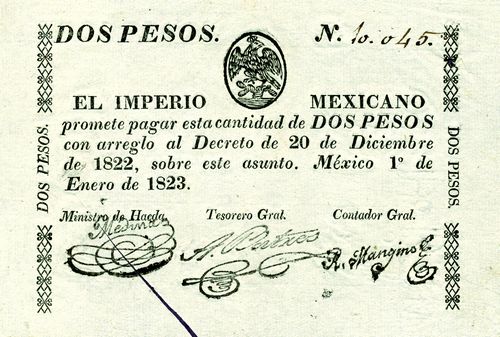

Depreciation and destruction

When a holder of this paper paid his obligations in the treasuries, treasury offices or customs, the latter had to disable the notes by diagonally cutting through the signature of the Minister of Finance to prevent their return to circulation, and to record the number, amount and name of the person who delivered it. Therefore, many of the surviving notes have such a cut. The subordinate offices reported monthly on the amount of amortized notes, after certification by a Treasury Judge or Subdelegate, to the treasury in the capitals, delivering the “dead paper” (papel muerto) so that once registered it would be incinerated and the offices of the capitals would do the same to the Ministry of Finance. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4. 10.447 In the meantime, it would be replaced with “live paper” (papel vivo).

A $2 note with a cancellation cut through Medina’s signature

Note that the 7 February count (above) called for the destruction of 23,022 unused notes and of 67,090 notes that lacked a stamp or numbering, as well as of any defective paper.

Estimates of the monthly amortizations made by Francisco José Bernal calculated between twelve and fourteen thousand pesos for public finance and six to seven thousand for others. In the Gaceta del Imperio of 11 March 1823 55,989 pesos were reported as amortized, namely 18,686 by the general treasury, 23,238 by customs, 8,076 by the tobacco office and 5,989 by the lottery. Gaceta del Gobierno Imperial de México, Tomo I, Núm. 35, 11 March 1823, p 130

Given the uncertainty about the future of the government, on 6 March, the treasuries were ordered to make a count of the stamped paper, sent to the provinces, amortized and in stock that they delivered on the 14th of that month with the following results: CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11.503-504

| Paper Money printed | On white paper | 1,535,000 |

| On bulls | 732,000 | |

| Total | 2,267,000 | |

| Paper money consigned | To provinces and handed over to commissioners | 434,450 |

| To addresses | 123,036 | |

| In payments and exchanges | 386,230 | |

| Paper money amortized | 68,794 | |

| Subtotal | 1,012,500 | |

| Existence in the Treasury | 1,254,000 | |

| In the possession of the manager Larraguibel | 400,000 | |

| Total stocks | 1,654,500 |

It is striking that at this time paper printed on papal bulls has already been recorded. Without being categorical in this statement, it can be thought that counterfeiting problems forced the government to replace the original paper money, which explains why they had collected white paper as mentioned above and even before the Republic, the Empire may have already printed some notes on obsolete bulls. One possible explanation for the fact that these Imperial notes on bulls are not known is that they would never have been sent to the treasuries and were destroyed before entering circulation.

A statement of account presented by Antonio Beltrán on 21 March has very similar figures, including a higher figure for money printed on bull paper, 860,000, which would show that between 14 and 17 March they continued to print on bullsLuis H. Flores, Nicaragua - Its Coins, Paper Money, Medals, Tokens, Imprenta Comercial La Prensa, Managua, 2002, pp. 161.

It should be noted that since February 1823 Antonio López de Santa Anna and Vicente Guerrero had taken up arms against the emperor under the Plan of Casa Mata, and he abdicated on 19 March.

On 3 April, the provisionally appointed Supreme Executive Power decided to suspend for the time being all payment with the paper money that was being falsified and proposed to collect the money in existence and exchange it for vales, as had been done in Puebla. At the time the reported amount in existence was 1,328,063 pesos. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11-512

On 14 April, a new decreeGaceta del Gobierno Supremo de México, Tomo I, Núm. 51, 17 April 1823, pp 191-192 was issued by which the Sovereign Constituent Congress ordered the printing press to suspend its manufacture; the treasuries to cease their issue and return to the central treasury the stocks and those collected, as well as to collect the stamps and paper held by the printer. Likewise, the obligation to collect and pay with this paper was ceased until the holders had changed it in the Treasury. Only for the purpose of exchanging the imperial notes, new notes would be printed on bull paper - with as many precautions as were convenient to prevent their counterfeiting - and a period of 15 days was established in the capital of the country and one month in the rest of the territory where certificates would be given to be exchanged later. I have not tried to make a similar analysis of the second issue, but it is worth noting that this one was very similar to the first: the denominations were the same and even two of the signatories, Treasurer Bartres and Accountant General Mangino, remain. Curiously although Minister de Medina remained in post until 26 June 1823 (according to Ludow), his signature no longer appears. The holders had to sign the notes on the back to identify whoever had a false one, which would be returned without any comeback against the treasury and the Ministry of Finance would keep a register of printed, issued and amortized paper. A count of the national customs between 1 and 18 April mentioned the amortization of 24,831 pesos. Gaceta del Gobierno Supremo de México, Tomo I, Núm. 82, 14 June 1823, p 312

Obviously, claims arose from multiple outstanding debts. The official gazette published an agreement of the emperor that recognized debts of salaries and loans of officials of the Ministry of Finance, signed by Minister Navarreteibid., Tomo I, Núm. 53, 22 April 1823, p 200 and days later the claims by the Plaza de Toros for the Emperor’s inauguration were made public, in which they referred to the existence of a lot of paper money. ibid., Tomo I, Núm. 55, 26 April 1823, p 209

Originally the Imperial paper money was changed in the different locations, but considering the ease in exchanging counterfeit notes, some officials were appointed as experts to identify the genuineness of the notes to be exchanged, in Mexico City, Manuel Araoz, Joaquín Piña and Mariano Larraguibel. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11-522 There is a systematic record of the exchange made in Mexico City through a book (Libro de Cambio) that registers more than a thousand people who exchanged a total of 257,758 notes (213,761 of one peso; 40,151 of two pesos and 3,846 of ten pesos) , for a total of 332,523 pesos. A transcript is available at: http://herzog.economia.unam.mx/hm/docs/COMENTARIOS AL LIBRO DE CANJE DE PAPEL MONEDA 1823.pdf Roxana Álvarez found that the new issue reached 600,000 pesos. The exchange of the old paper for the new one was carried out until well into the year 1824. We do not have precise information about the date of the definitive cessation of this paper.

On 26 April there was mention of an existence of 1,929,978 pesos in useful, useless and amortized notes that could begin to be incinerated. Several precautions were proposed to prevent fraud: punching themCEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11-519, recounting them and recording their numbers, or keeping them in strongboxes under three keys from where they would only be extracted to be burnt.

Records from 16 to 24 March mention the burning of 1,729,978 pesos. According to Bermudez’s counts, if we add to this amount 200,000 pesos from a first incineration and two subsequent certifications of 3,338 pesos (Zacatecas) and 5,503 pesos (Guanajuato), 1,938,819 pesos must have been destroyed. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.12-632

On 16 May the Sovereign Constituent Congress instructed that holders of paper money, changed in accordance with the decree of 14 April, may use it to make up to one sixth of the payments they owe to customs and made their circulation free in the case of payments and contracts between individuals. It also reaffirmed that their deactivation should be guaranteed when they were redeemed. In the communication from the Ministry of Finance, reference was maintained to the need to make the cut in the signature of the Minister of Finance and to continue keeping an account in a notebook of the number, value and individual who delivered each note. Circular No. 70, CEHM, I-2.14-38 1145, available at httpd://www.papermoneyofmexico.com/documents/distrito-federal/18230611-df

As previously, these changes raised requests that they not be applied and new doubts. Among the former, stewards, representatives of communities, confraternities and pious works asked the Sovereign Congress to be exemptGaceta del Gobierno Supremo de México, Tomo I, Núm 70, 24 May 1823, p 261, and among the latter, whether it should apply to both maritime and land customs or only to the latterCEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.1.561 or whether all payments to the Treasury should be made with one sixth in paper money and or only those corresponding to the Public Treasury, so it was decided that as long as Congress did not stipulate it, only the latter were and in the absence of explicit prohibition it was indicated that it was not obligatory that one sixth of the payments be made with this means of payment. Circular No. 73, CEHM, I-2.14-38 1153 On 31 May a decree was published reaffirming these positions including the need to invalidate the banknotes by making a cut in the signatureCEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11-521 and at the beginning of June while establishing a commission of amortization in the Sovereign Congress, several circulars were issued in the same sense (CEHN, I-2.15-38. 1153 and 1159) and where they clarified that the use of paper money was not essential for the payment of that proportion, but that those who wanted could do it entirely in cashCEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11-522 and in September the Minister of Finance Arrillaga issued another decree in which it was established that merchants would be obliged to pay one sixth of the national duties owed to internal customs in paper money, It did not include the other fees that they collected such as municipal or corporate fees that would be charged in cash. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.1.538 Doubts continued to prevail since in December 1824 they were still wondering whether the notes should be admitted for the payment of the dues of the States (México and Veracruz) – new Territorial division of the Republic - or only of the Federation. CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.1.570-577

Although the records of incineration of the certificates changed and amortized between July 18 and 23, available in the CEHM, add up to only 1,460,528CEHM, Ramón Beltrán Collection, Fondo VIII-4.11.525, 528, 527, 529, 531, 532, 533, counts of the national customs from February to August 1824 mention the amortization of 79,361 pesos in paper money for the following amounts: Aguila Mexicana, Año 1, Núm 330, 9 March 1824; Núm 364, 12 April 1824; Año 2, Núm 23, 7 May 1824; Núm 61, 14 June 1824; Núm 91, 14 July 1824; Núm. 116, 8 August 1824; Num 152, 13 September 1824

| Month | Total (pesos) |

|---|---|

| February | 18,565 |

| March | 11,708 |

| April | 13,123 |

| May | 6,270 |

| June | 5,865 |

| July | 9,425 |

| August | 14,405 |

And a communication from the general commissioner of Veracruz suggests that at least until August 1825 they continued to circulate and it is said, (without having found any document to prove it), they continued to be accepted in some provinces such as Coahuila and Texas until the 1830s.

I would like to thank Pablo Casas, Rogelio Charteris, Ricardo de León, Manuel Galan, Luis Gómez-Wulschner, Alan Luedeking and Siddartha Sánchez for their guidance and willingness to share some copies that allowed me to complement and illustrate this study.

Antonio de Medina y Miranda was born in Veracruz in 1771. In his teens he joined the Royal Navy, and later held various government posts and the military and business experience accumulated during the years of the War of Independence were fundamental to his subsequent positions, which began during the last virreinal administration as Comisario de Guerra in charge of the office of Cuenta y Razón which received all provincial income.

Antonio de Medina y Miranda was born in Veracruz in 1771. In his teens he joined the Royal Navy, and later held various government posts and the military and business experience accumulated during the years of the War of Independence were fundamental to his subsequent positions, which began during the last virreinal administration as Comisario de Guerra in charge of the office of Cuenta y Razón which received all provincial income. Rafael Mangino y Mendívil was born in Puebla in 1788. After service in the army and travelling through Europe he was employed in the Administración de Tabacos in San Luis Potosí and, in 1819, as secretary of finance in Valladolid (today Morelia). When Iturbide occupied Puebla in August 1821 Mangino offered his services and was named Tesorero General of the Army of the Three Guarantees. As President of the first Congress he was the person who actually crowned Iturbide as Emperor. This first Congress appointed him as Contador Mayor de Hacienda. He was minister of Hacienda on two occasions, in 1830 to 1832 and again in 1836, where he increased revenues, organised the oficinas recaudadoras and established the Dirección General de Rentas.

Rafael Mangino y Mendívil was born in Puebla in 1788. After service in the army and travelling through Europe he was employed in the Administración de Tabacos in San Luis Potosí and, in 1819, as secretary of finance in Valladolid (today Morelia). When Iturbide occupied Puebla in August 1821 Mangino offered his services and was named Tesorero General of the Army of the Three Guarantees. As President of the first Congress he was the person who actually crowned Iturbide as Emperor. This first Congress appointed him as Contador Mayor de Hacienda. He was minister of Hacienda on two occasions, in 1830 to 1832 and again in 1836, where he increased revenues, organised the oficinas recaudadoras and established the Dirección General de Rentas.